by Sasha Alyson

In the past few decades, faced with evidence that a lot of money was going out the door without much to show for it, donors have increasingly pushed for more evaluations of aid programs. These evaluations don’t get much attention – you’ll soon see why – but they often present a very different picture from what reaches the public.

Save the Children bills itself as “the world’s leading expert on childhood.”(1) Here’s one finding about its Literacy Boost program in Zimbabwe. The study compared LB schools (those that got the Literacy Boost program) with those that did not:

“At the beginning of the school year, there were no statistically significant differences between girls and boys performance in LB schools…. Over the school year, girls made fairly large gains in all skill areas… but boys made small or negative gains in over half the skill areas.“(2)

Zimbabwe was not an outlier. In the Philippines, Save the Children’s report warned of “A trend in which the sample of girls outperformed the sample of boys in various sub-tests…. Given this, Literacy Boost should provide special measures to engage and support boys where their knowledge is lagging behind girls.”(3)

And in Sri Lanka: “The girls significantly outscored the boys on nearly every sub-skill measured…. grass-roots advocacy campaigns should be pursued to help boys close the gap with their female peers.”(4)

Others were finding the same thing. The Global Partnership for Education is a major source of funding through which the West shapes education policies in developing regions. An outside evaluation of GPE’s work in Senegal found that “Gender equality has substantially improved for girls at various points in time for most basic education indicators in Senegal, but the situation has today shifted with growing inequalities noted for boys in many areas…. [L]ittle attention appears to have been given to underperforming boys in national plans and policies.”(5)

A 2018 UNESCO report argued that “addressing boys’ disadvantage and disengagement in education is an essential part of a response to the challenge of gender inequality, in education and beyond.”(6)

They all understand the problem. What are they doing about it? Let’s look.

A Google search

I typed “girls education” into Google. The top result was an ad from Plan International, a large NGO with a web page called “girls-education” which has a DONATE button so you can help them fix the crisis they describe.

Next on Google are two UNICEF pages, both called “girls-education,” both with a DONATE button. And then comes a flood of NGO listings: Save the Children, World Vision, Room to Read, CARE, and more, nearly always with the same formula: A page called “girls-education” presents a dire picture of oppressed girls, with a button so you can donate to help this charity fix it. Of the first 20 Google results, 16 are NGOs and U.N. agencies that portray a crisis and ask for your donation.

Then I searched for “boys education.” The top 20 results showed not a single organization asking for your donation so it could improve education for boys. There were stories – “Why Boys Aren’t Learning” and “Why Are Boys Falling Behind at School?” – but no NGO fundraising appeals. I continued through 20 Google pages – 200 results. Nothing. When it came to foreign agencies setting up programs for them, girls were 16 for 20. Boys were 0 for 200.

Surprise! It’s not girls who are disadvantaged.

Why the huge gap? Girls in the past did often face discrimination as far as school attendance, though it’s dubious that donor-driven NGOs were the best solution. As U.N. policies have been put in place, evidence overwhelmingly shows that schooling has gotten worse for boys and girls alike in the global South.

But today, boys and girls are enrolled in roughly equal numbers. There are some variations by region and age, but worldwide, says the U.N., there are about 131 million girls out of school — and 133.4 million boys.(7)

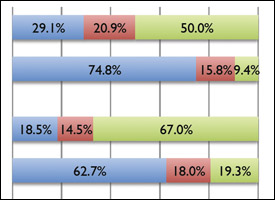

And academically? Surely that matters more than enrollment. Girls are well ahead, in the global South and North alike. In math, boys and girls score about equally – girls are doing slightly better. In reading, girls are consistently ahead.(8)

Yet the world is told, again and again, that girls face severe discrimination in developing regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Frequently I talk with well-intentioned Americans, Europeans, and Australians, who are eager to explain that girls face great discrimination in attending school, and that girls’ education is the key to the problems of the global South. They are neither as enlightened nor as knowledgeable as they believe, they have simply swallowed some trendy aid groupthink.

Here’s what happens next: The charities that collected donations for “girls education” must show donors they’ve been busy. Otherwise, the next donation goes to somebody else on that Google list. The charities don’t need to show results; merely that they did something. Donors won’t investigate whether it was helpful, harmful, or utterly irrelevant. Just give it a good name.

World Vision has its Strengthening School Community Accountability for Girls Education (SAGE) project in Uganda, which “is working to reduce secondary school dropout among girls ages 13-19 in 151 schools in 10 districts.”

Save the Children’s Keeping Girls in School program in Malawi aims “to increase the number of girls who completed their primary school education” by giving cash to the caregivers of girls who attended school.

The U.K.’s Department for International Development boasts that its Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) is “the largest global fund dedicated to girls’ education,” aiming “to get at least 1.5 million out-of-school girls into education and keep them in school.”

Note one common theme: A focus on getting girls into school, and keeping them there.

The aid industry has finally admitted that despite its quarter-century focus on school enrollment, many children learn little or nothing in the schools they are being shoved into. And it’s not hard to understand why. In the past, parents might have been angered that their daughters went to school and learned nothing. They might have pushed for change. Now, Save the Children is paying parents to be sure their daughters attend. That won’t improve the schools but it will lessen the anger. In fact, it seems likely to reduce the pressure to improve schools.

Why, then, the continued focus on enrollment, rather than good schools?

Three reasons seem dominant. First, it brings in donor money, and that’s the bottom line. Second, these agencies have figured out how to fill schools; they have no idea how to improve school quality. And finally, they don’t really want the world looking too closely at whether children actually learn anything. That would draw attention to how much school systems in much of the developing world, under the growing influence of U.N. and NGO programs, have deteriorated.

Throwing boys under the schoolbus

By pushing girls’ education above all else, the aid industry teaches another, unstated lesson: Boys don’t matter.

Aid agencies want to shape policy. They need to set up new programs. But there are only so many concerns that a teacher or administrator can address. If you’re an NGO, how do you ensure that your new program gets attention?

That’s easy. You bribe people — but in a socially acceptable way. A common approach is to pay generous per-diem expenses to teachers and administrators who attend a workshop about whatever you think is important. Girls’ education, for example.

Honestly, it’s a lot more pleasant to teach 8-year-old girls than boys, anyway, and now you’ve been told it’s the morally right thing to do, and you’re getting treats and praise from an international agency which surely knows what it’s doing. And so teachers and administrators follow the script. If that means throwing some boys under the schoolbus, well, they shouldn’t have been so rowdy.

Who should set a nation’s priorities?

Discrimination of many types should be ended, in the global North and South alike. The U.N. prioritizes gender over economic and racial equality. Far less often does it address the great differences between those born into richer or poorer circumstances. And there is wide discrimination against ethnic and religious groups that are out of favor, against those with mental or physical challenges, as well as urban-rural splits, and much else. Balancing these priorities is hard, there are never enough resources.

But should national policies and priorities be set by those in the country affected, who understand their society, who will live with the consequences, who can quickly react when circumstances change – or by faraway donors, based on whatever they’ve been trained to believe by dollar-hungry Western agencies?

Phrased like that, it doesn’t seem like a difficult question.

Comments from Twitter

We announced this story on Twitter, where readers made these comments. Please add your own comments at the bottom of this page.

Mhofu wekwaSeke, @albertzinyemba: I worked with Save the Children for ten years in Zimbabwe as an education official. They always came with preconceived solutions to our problems.

Abdisalam Yassin, @AbdisalamYassi1: All INGOs do more harm than good and are therefore bad. But some are worse than others. In our experience in Somaliland, Unicef is worse than Save the Children. At least Save the Children sometimes listens to local officials and local communities. Unicef is beyond the pale.

I am hot dodo and I, @RedTemi: In the places I’ve lived I’ve found there is a higher advocacy for getting young girls into school than boys, regardless of the school’s standards. Most of these schools are UNICEF or World-Bank funded.

Gainmo, @Gainmo2: Boy child needs a hand too.

CALMDOWN, @TiruHilarylee: This is soooo true, in the long run boys are being forgotten.

HilaryEllary, @HilaryEllary: Girls are being groomed – complying with the system or maybe consciously using the system. Boys are refusing to be brainwashed and rebelling by behaving ‘anti-socially’ – actually anti-system.

Notes and Sources

1. To call yourself “the world’s leading expert on childhood” is quite a brag, but Save the Children has enthusiastically adopted this slogan. The organization uses this phrase dozens of times on its various websites, everywhere from the U.S.A. and Canada, to New Zealand and Hong Kong. The phrase is then parroted by others, including New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, as if it were his own words reporting an established fact rather than an advertising line.

2. Save the Children: LB 2nd year Endline, Zimbabwe, by Christina Brown. March 2014.

3. Save the Children: Literacy Boost Philippines: Metro Manila Baseline Report, by Jarret Guajardo, Rachael Fermin, Cecilia Ochoa, and Amy Jo Dowd, January 2013.

4. Save the Children: Literacy Boost, Sri Lanka, by Elliott Friedlander, Carolyn Alesbury, Nilantha Fernando, Helmalie Vitharana, and Kaysuya Yoshida. March 2013.

5. Summative Evaluation of GPE’s Country-level Support to Education, Batch 4, Country 11: Senegal, Final Report, August 2019. Universalia Management Group.

6. Achieving Gender Equality in Education: Don’t forget the boys. UNESCO/GEM policy paper 35, April 2018.

7. These out-of-school figures are from 2015, and are still widely used – for example, by the Global Partnership for Education. I cannot find newer breakdowns, and here’s a plausible reason: With the great push to get more girls into school, the girl-to-boy ratio is probably growing – yet aid agencies base their fundraising on their claim that girls face great discrimination. If boys are now more affected, they’d prefer that the world not know.

8. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database gives breakdowns by country, where available. Regional and worldwide averages are from More Than One-Half of Children and Adolescents Are Not Learning Worldwide, by UIS, September 2017. In other stories, I’ve criticized UIS’s poor handling of statistics and I’d prefer to use a different source, but there’s not one. In the case of the country-by-country comparisons, numbers come from the individual countries and UIS is simply compiling them. In the case of developing regions, nobody has good data and UIS pretends to have a better picture of the situation than it really does. I use their data here because nothing else is available. Furthermore, it shows that even by its own numbers, the aid industry is fabricating a problem for fundraising purposes.

Cartoon at top by Chittakone Vilayphong.

Related stories

Right: Masters of Deceit. Raising funds for “girls’ education” has become big business…. and remarkably often, the aid industry has crossed the line into deceit and dishonesty.

Right: The campaign against reading. The aid industry says it promotes reading. But its actions — such as dumping unwanted books from the USA — are motivated by self-interest, and consistently undermine reading in the global South.

Right: Schooling vs. education. The United Nations has convinced much of the developing world that getting more children enrolled in school is the same as expanding education. The consequences have been devastating.

Other stories of interest

Right: Bribes. Unicef gave vehicles to Zimbabwean officials “to help review the school curriculum.” Nonsense. Thinly-disguised bribes ensure a warm welcome for foreign aid staff, who can then keep drawing big salaries.

Right: What would make a better future? There are ways that wealthier countries can genuinely help others, if they want to. Give the aid money directly to the poor, for example. Here are ideas.